Minced Oaths

Minced oaths get a bad rap. To self-respecting swearologists, they’re often looked down upon as low-fat, sugar-free swear substitutes. To many of the prudes they’re supposed to placate, even minced oaths are too rude. But to me, an intellectual, minced swears are friggin’ cool as heck, and ruddy interesting to boot. The low-fat/sugar-free analogy is a bad one, actually. Whereas ersatz foods are designed to be almost indistinguishable from their full-flavored counterparts, minced oaths are specifically constructed to avoid being mistaken for the real deal. Consider “fuck” and its most commonly used alternatives:

- frig

- frick

- freak

- fudge

- flip

Undoubtedly there are phonological constructions much closer to the original word which we could use instead. But no one says “fub” or “fut”, and “fug” – while sometimes used – is rare. Notice that each of the words listed above has undergone at least two phonetic transformations in order to achieve its minced form. The vowel sounds in every example besides “fudge” have been altered. The ending consonants have often been shifted. Most interestingly, almost every example includes an alveolar approximant (r or l) inserted after the first, most identifiable letter.

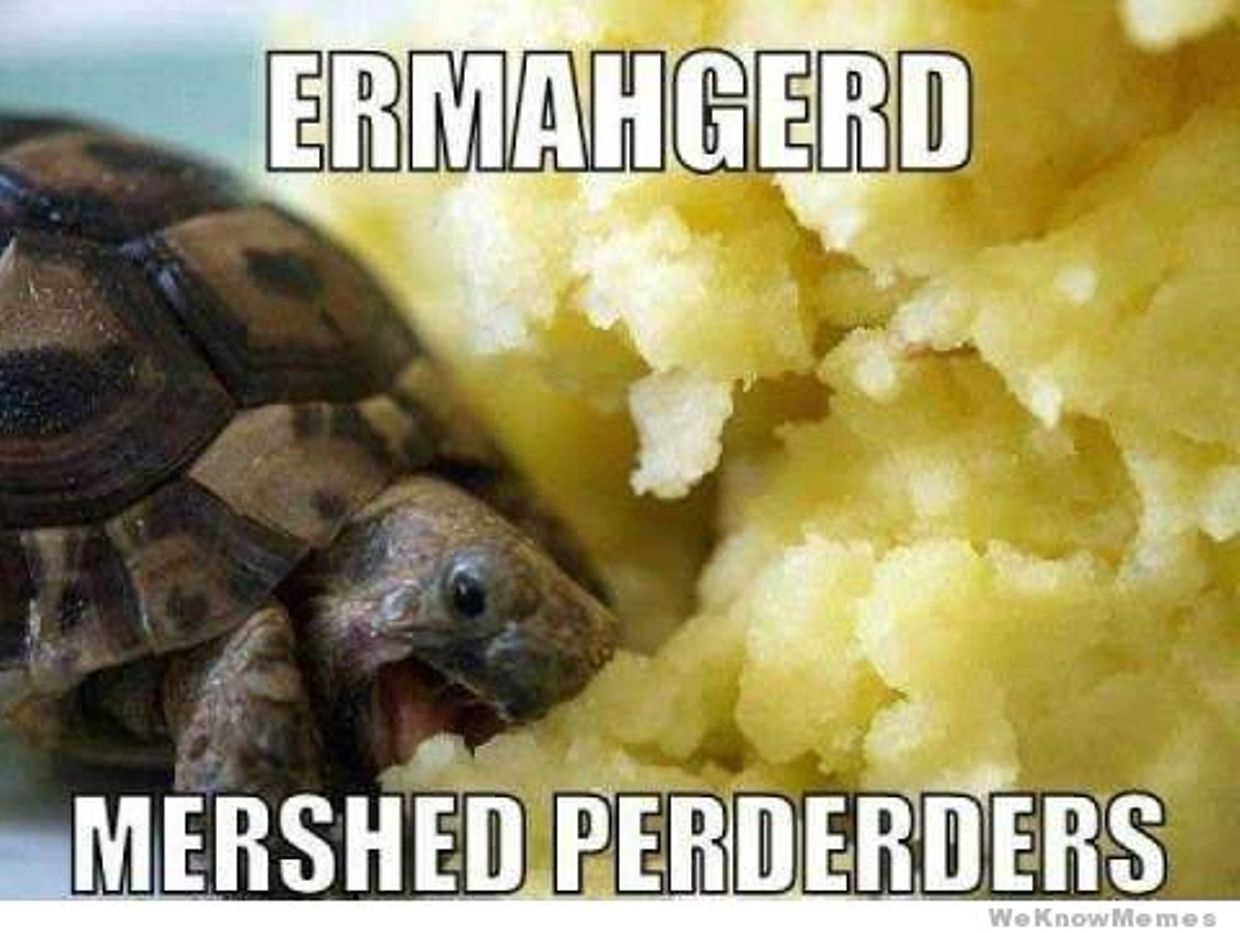

Now go look up “food spelled wrong meme.” Notice that the exact same techniques have been used.

MERSHED PERDERDERS = Mashed Potatoes, with half the vowels shifted, t’s swapped for d’s, and r’s inserted. This is what we do when we want everyone to know we’re spelling something wrong on purpose. It’s also what we do when we want to make absolutely sure that we are pronouncing something incorrectly.

Now let’s look at some of the most common mincings of “damn”:

- Dang

- Deng

- Drat

- Darn

- Dag

Notice that all five have completely removed the “m” which dominates the ending of the original word. Without the “m” the “n” sound changes completely. But we don’t say “Dan” when we’re mad, unless we’re mad at a person named Dan. That’s still not enough of a misspelling. We’ve either got to insert an “r” (there’s that alveolar approximant again), or add a “g” to the end. “Ng” is a reasonably common phoneme in English, but “mg” is basically unheard-of. Nobody’s gonna be mistaking these words for their more-offensive cousin.

Ultimately, that’s the purpose of mincing oaths. It’s not just about technically obeying the rules of polite conversation – about convincing other people that we aren’t saying bad words. It’s also about convincing ourselves that what we’re saying isn’t that bad. Minced oaths allow us to enjoy the cathartic nature of swearing, while stripping the words of any taboo meaning or potential for abuse. Notice that while “aw, fudge” sounds relatively okay, “I want to fudge you on the counter” sounds downright ridiculous. “Gosh darn it” sounds quaint, but “darn you to heck” sounds pretty silly.

There are plenty more minced oaths in English, and not all of them follow the phonological rules I’ve discussed above. Perhaps one day I’ll create a guide to mincing your own oaths, so that we can invent a whole new class of minced epithets. For now, however, my point is this: minced oaths aren’t low-fat cusses. They’re swears with the safety on. Just as a gun’s safety makes sure we only use it when we really mean to, minced oaths allow us to be intentional about our swear usage. So consider giving a few frigs and freaks instead of fucks, so that when only fucks will do, you still have some left to give.